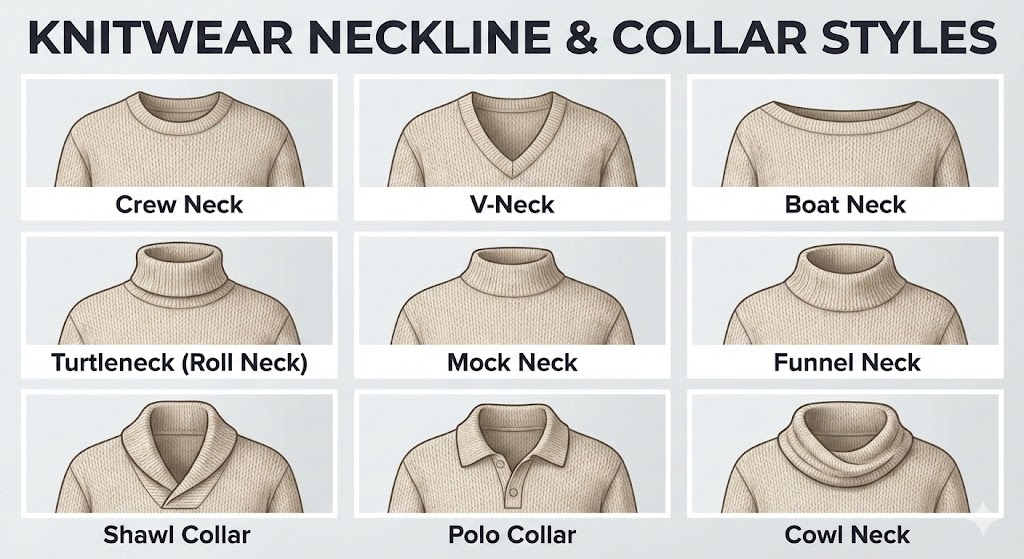

Mastering Knitwear Architecture: A Guide to Types Knitted Necklines & Collars

Define the silhouette of your collection with precision. A comprehensive resource on collar construction, gauge suitability, and style terminology for modern manufacturing.

Table of Contents

The Foundation of Knitwear Silhouette

In knitwear design, the neckline is not just a detail—it is the structural anchor of the garment. Unlike woven fabrics, knitted collars require precise engineering of tension, elasticity, and weight distribution. Whether you are developing a fully fashioned cashmere line or a cut-and-sew jersey collection, choosing the right neckline dictates the garment’s drape, functionality, and market category. This guide categorizes industry-standard styles with technical insights to streamline your product development process.

The Essentials (Closed Necklines)

The Crew Neck

The industry standard. A round, close-fitting neckline sitting at the base of the throat. Usually finished with a 1×1 or 2×2 rib band to ensure elasticity and shape retention. Best for sweater designs.

Pro Tip: For a premium finish, request a “tubular cast-off” on the neck trim to prevent the edge from flaring out over time.

The V-Neck

A V-shaped opening that creates verticality. Styles range from the “Standard V” (ending at the clavicle) to the “Deep V” (ending at the chest line).

Pro Tip: The “mitered” V-neck (where stitches converge at the center point) requires slower knitting time but offers a significantly higher quality look than a “lapped” V-neck.

The Boat Neck (Bateau)

A horizontal slit neckline running shoulder-to-shoulder, inspired by French naval uniforms. It sits high on the chest and minimizes the visual appearance of the neck trim.

Pro Tip: Boat necks require careful shoulder construction (often a “saddle shoulder” or “drop shoulder”) to prevent the fabric from bunching at the armhole.

High Collars & Lofted Structures

The Classic Turtleneck (Roll Neck)

A high, tubular collar that extends up the neck and folds over itself. It provides maximum warmth and is a staple in Fall/Winter collections.

Pro Tip: Ensure the neck opening has sufficient stretch (high elasticity yarn) to fit over the head comfortably without losing its shape (recovery).

The Mock Neck

A high collar that stands upright but does not fold over. It is typically shorter than a turtleneck and offers a streamlined, modern silhouette.

Pro Tip: Ideal for mid-gauge knits where a full fold-over would be too bulky. Often used in performance and athleisure knitwear.

The Funnel Neck

An extended neckline that is knitted as a continuation of the body panel, rather than a separate attached trim. It stands away from the neck, creating a relaxed, architectural look.

Pro Tip: This style works best with stiffer yarns or tighter gauges to ensure the “funnel” stands up rather than collapsing.

Statement Collars & Complex Construction

The Shawl Collar

A turned-over collar that forms a continuous curve with the lapel, crossing over at the chest. It adds significant visual weight and luxury to cardigans and heavy pullovers.

Pro Tip: “Racking” stitches are often used here to create a dense, thick fabric that holds the shawl shape. This is a high-consumption style regarding yarn usage.

The Knitted Polo Collar

A flat, turned-down collar featuring a placket (button or zipper). Unlike cut-and-sew polos, a fully fashioned knit polo has an integral collar linked to the neckline.

Pro Tip: The transition from the body to the placket is the critical quality marker. Look for “fashioning marks” at the collar base for a sign of high-end manufacturing.

The Cowl Neck

A generous neckline with excess fabric designed to drape in soft, rounded folds. It relies on gravity and yarn fluidity for its shape.

Pro Tip: Best produced in fibers with high drape (like Viscose, Silk blends, or Alpaca) rather than lofty, stiff wools.

Quick Reference: Collar Construction Matrix

| Collar Style | Warmth Level | Yarn Consumption | Best Production Method |

| Crew Neck | Low | Low | Fully Fashioned or Cut & Sew |

| Turtleneck | High | High | Fully Fashioned (Tubular) |

| Shawl Neck | High | Very High | Fully Fashioned |

| Cowl Neck | Medium | Medium | Cut & Sew or WholeGarment |

Standard Collar Pairings by Garment Type

Select the right neckline architecture to enhance the functionality of your silhouette.

- Sweaters generally favor high-stability styles like the Crew or Turtleneck for warmth and retention.

- Cardigans are best suited for Deep V-Necks and Shawl Collars to accommodate layering.

- Knitted Dresses allow for wider, elegant cuts like the Boat Neck or Cowl, while lightweight Tops often utilize structured Polo collars or open Scoop necks for a modern finish.

Ready to Develop Your Knitwear Collection?

From selecting the right gauge to finalizing your tech packs, our team helps you navigate the complexities of knitwear manufacturing.

FAQs of Neckline & Collars

While they look similar, the construction is different. A Mock Neck is typically a separate rib trim attached to the neck opening (similar to a shortened turtleneck). A Funnel Neck is usually knitted as an integral extension of the body panel without a separating seam. From a manufacturing standpoint, Funnel Necks require specific tension adjustments to ensure they "stand up" without the support of a seam, often requiring tighter gauges or stiffer yarns.

This is usually an issue of "recovery." To prevent a Turtleneck from sagging, we recommend "plating" (knitting together) a fine strand of Spandex or Lycra with the main yarn inside the rib structure. This adds invisible elasticity. Additionally, using a 1x1 Rib structure generally offers better retention and elasticity than a Jersey roll neck.

The Crew Neck is generally the most cost-effective. It consumes the least amount of yarn and has the fastest "linking" (assembly) time. In contrast, styles like the Shawl Collar or Hoodie significantly increase the garment's price because they require more raw material (yarn consumption) and longer knitting times on the machine.

Look at the point of the V. In high-end manufacturing, we use a "Mitered V-Neck," where the stitches converge perfectly at the center point with a decrease line. Cheaper "Cut & Sew" productions often use a "Lapped V-Neck," where one side of the collar band simply overlaps the other at the bottom. The Mitered finish lies flatter and signals a Fully Fashioned production.

No, a true Shawl Collar requires a Double Bed (V-Bed) knitting machine. This is because the collar usually requires a "racked" rib structure or a double-knit construction to provide the necessary thickness and volume to drape correctly. Single-bed machines cannot produce the reversible, balanced structure needed for a shawl lapel that is visible on both sides.

A roll neck has a long, soft collar that folds or rolls over itself, sitting close to the neck. A funnel neck has a shorter, structured collar that stands upright and does not fold over. Roll necks feel softer and more insulating, while funnel necks look more modern and provide a cleaner silhouette.

A polo neck has a tall, close-fitting collar designed to be worn folded or extended, fully covering the neck. A funnel neck is shorter and looser, standing away from the neck without folding. Polo necks offer more warmth and a classic look, while funnel necks are lighter and more casual.